KLI Colloquia are invited research talks of about an hour followed by 30 min discussion. The talks are held in English, open to the public, and offered in hybrid format.

Join via Zoom:

https://us02web.zoom.us/j/5881861923?omn=85945744831

Meeting ID: 588 186 1923

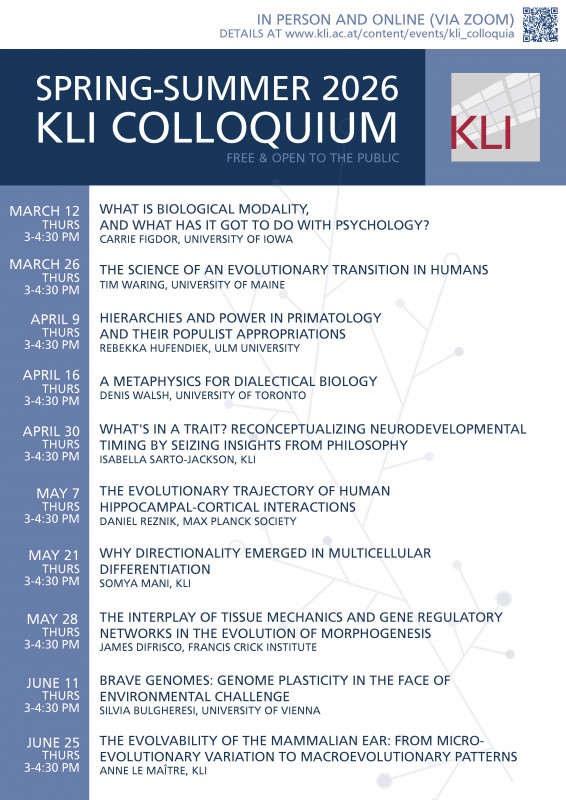

Spring-Summer 2026 KLI Colloquium Series

12 March 2026 (Thurs) 3-4:30 PM CET

What Is Biological Modality, and What Has It Got to Do With Psychology?

Carrie Figdor (University of Iowa)

26 March 2026 (Thurs) 3-4:30 PM CET

The Science of an Evolutionary Transition in Humans

Tim Waring (University of Maine)

9 April 2026 (Thurs) 3-4:30 PM CET

Hierarchies and Power in Primatology and Their Populist Appropriation

Rebekka Hufendiek (Ulm University)

16 April 2026 (Thurs) 3-4:30 PM CET

A Metaphysics for Dialectical Biology

Denis Walsh (University of Toronto)

30 April 2026 (Thurs) 3-4:30 PM CET

What's in a Trait? Reconceptualizing Neurodevelopmental Timing by Seizing Insights From Philosophy

Isabella Sarto-Jackson (KLI)

7 May 2026 (Thurs) 3-4:30 PM CET

The Evolutionary Trajectory of Human Hippocampal-Cortical Interactions

Daniel Reznik (Max Planck Society)

21 May 2026 (Thurs) 3-4:30 PM CET

Why Directionality Emerged in Multicellular Differentiation

Somya Mani (KLI)

28 May 2026 (Thurs) 3-4:30 PM CET

The Interplay of Tissue Mechanics and Gene Regulatory Networks in the Evolution of Morphogenesis

James DiFrisco (Francis Crick Institute)

11 June 2026 (Thurs) 3-4:30 PM CET

Brave Genomes: Genome Plasticity in the Face of Environmental Challenge

Silvia Bulgheresi (University of Vienna)

25 June 2026 (Thurs) 3-4:30 PM CET

Anne LeMaitre (KLI)

KLI Colloquia 2014 – 2026

Event Details

Zoom link for registration:

Deadline for the registration with Zoom is 3 pm on the day of the talk.

Please take note that nobody will be admitted in the room after 5:05 pm.

Topic description / abstract:

Collecting biological samples among a remote-living group of hunter-gatherers is no small task. It is also one that is increasingly contentious with regard to the ethical awareness of those conducting such work. In the last decade, there has been a call for social, life, and biological scientists to expand their data collection beyond so-called WEIRD (western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic) populations, and incorporate what is commonly referred to as “field work” in their research agenda to better inform on the panoply of human experiences. But conducting cross cultural research is not a lateral jump from field biology, even for trained field scientists. The need for accountability and equability in the participation of work and benefits outcomes adds an ethical dimension to hypothesis driven experimental research. New technological advances means that bio-technological applications are able to springboard directly from basic research (indeed, are often the stated agenda of much basic research). This technological capacity is currently outpacing the ethical tools accessed by practitioners of human biological research, from field to bench to desk. Increasingly, short-term researchers, most of whom have little to no ethnographic or ethical training, are collecting, storing, and sharing large-scale biological data. While scholars in Social and Cultural Anthropology have long acknowledged that such endeavors are rooted in racist or exploitative capitalistic ideas, those in more biologically oriented disciplines have been resistant to the notion that their practices of data collection, storage, and publication are tacitly supporting colonial and imperialist practices – even in the 21st century. In the disciplines of genetics and genomics, the bioethics of working with Indigenous communities have begun to gain traction – yet microbiome sciences are woefully behind. A (regrettably) slow-dawning insight, coming from our own experience in conducting microbiome research with the Hadza of Tanzania, was the complete non-utility of the objectives of our research for the people from which this research was made possible. At what point was there a partnership of contractual work brokered equitably between parties? Here, we add to the growing dialogue of best practices when working with Indigenous communities and focus our discussion on the collection of microbiome data, addressing the possibility of findings for clinical management and product development, and the need for returning results. We address the many faces of fieldwork, describe what it can look like, including examples from our own experiences, and discuss how we can do better. The microbes of Indigenous peoples have become a valuable commodity and are envisioned as a panacea for microbiome-targeted therapeutics benefitting those in the post-industrialized west. Thus, we aim to highlight the urgent need for ethical responsibility of data collection and management when working with these communities. We argue that transparency and disclosure of agendas is the way forward, where the knowledge of each party’s needs allows for a commensurate reciprocal working relationship.

Biographical note:

Stephanie Schnorr is a biological anthropologist who studies the role of diet and the gut microbiome in human evolution. Stephanie began this line of inquiry during her dissertation by studying wild underground storage organs (or tubers) consumed by modern human hunter-gatherers, in particular by the Hadza of Tanzania, in which the microbiome plays a critical role. After her PhD, Stephanie began to focus more specifically on microbiomes in anthropology at the Laboratories of Molecular Anthropology and Microbiome Research. While there, she trained in methods to research ancient microbiomes as well as the microbiome of edible termites, and has since moved on to pursue a wide variety of projects on topics ranging across human diet, digestion, physiology, and the gut microbiome. Stephanie holds an NSF Postdoctoral Fellowship out of the University of Nevada, Las Vegas to study the evolutionary conditions surrounding a selective increase in the human alpha-amylase gene copy number compared to other extant hominids and archaic humans. This line of research delves into the relationship between humans and starch-containing foods under the premise that these starchy foods were essential for early hominin occupation of savanna-mosaic environments, as well as ancient human migrations to foreign environments and their ability to cope with major ecological upheavals. Stephanie continues to work on these varied topics of diet and microbiome in human evolution as these occupy core foci of her general interest in research on biological symbioses, human physiology, and brain development.

Alyssa Crittenden is an Associate Professor in the Department of Anthropology and Adjunct Associate Profession in the School of Medicine at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. She studies the relationship between human behavior and the environment (ecological, political, and social), seeking to better understand the links between diet, reproduction, growth and development, and maternal, infant, and child health and behavior. Her research interests fall within the domains of Biological Anthropology, Behavioral Ecology, Political Ecology, Medical Anthropology, and Applied Evolutionary Anthropology.

Most of her research has been done in collaboration with the Hadza of Tanzania, East Africa — one of the world’s last remaining hunting and gathering populations — who she has worked with since 2004. She is currently working with members of the Hadza community to explore how women and children’s health is impacted by environmental change, political policy, shifts in diet composition, and ethnotourism. Dr. Crittenden has also recently begun several large-scale studies on the behavioral and demographic characteristics of co-sleeping mothers (who bedshare with their infants) all around the world, including in the US. Her work is published in top-tier academic journals as well as highlighted in popular outlets, such as The New York Times, Smithsonian, National Geographic, the BBC, Psychology Today, and on National Public Radio. She is committed to the open science movement and works to share her research findings with public media domains. Alyssa Crittenden is currently an Associate Professor and the Graduate Coordinator in the Department of Anthropology and Co-Director of the Nutrition and Reproduction Laboratory at UNLV.