News Details

“... my suggestion would be more general: (1) remain observant of emerging issues and challenges that come from your specific process and (2) develop co-working methods that not just address these issues, but are also more generative.”

“Diversity Regained: Precautionary approaches to COVID-19 as a phenomenon of the total environment” (2022) is a large-scale collaboration project developed by fellows at the KLI and their collaborators. The aim of this interview is to bring out a remarkable aspect of this paper— the unique trans-disciplinary collaboration methods and tools developed by the team to meet the challenge of short-term, cross-disciplinary collaborations. Two methods were developed: a “thought anchor” to streamline a cohesive goal between the different sub-topics, each carried out by a different team, and a “concept relation game” that explicitly sought to identify the connecting points between each topic/team.

Knowing how we can effectively and efficiently carry out interdisciplinary work is especially pertinent in the current academic climate, where more and more teams consist of short-term, multi-disciplinary collaborators, many of whom are early-career scholars employed on contingent contracts. Some studies are carried out within the span of a single conference or week-long working group. Others are funded by short-term (a few months to half a year) grants. Many of these teams are mid-sized, about a dozen people. Projects of this kind rarely come from discussions workshopped throughout the years by permanent faculty within the same discipline. There is thus an urgent need to develop the means to efficiently focus on a joint issue and effectively weave together participant knowledge and skillsets.

The team behind Diversity Regained presents us with a fine example. The paper is a follow-up piece of “Diversity Lost: COVID-19 as a phenomenon of the total environment” (2021), which identified the pandemic as a phenomenon stemming from a deeper problem: the loss of diversity in the total environment (aka the biosphere, the geosphere, and the anthroposphere). Following this diagnosis, “Diversity Regained” proposes precautionary and systemic approaches to proactively, not reactively, meet future global challenges. We interviewed one of the co-leads Orsolya Bajer-Molnár to gain insight on the specific challenges they had, the tools they developed to resolve these challenges, and suggestions they have for those seeking to apply these tools to their own project.

Lynn Chiu: Orsolya, this project is quite the undertaking! You have here a team of very diverse scholars working on issues spanning the total environment. What are some of the main challenges your team encountered?

Orsolya Bajer-Molnár: The big-picture challenge is to figure out how we can bring together the expertise and disciplines that are distant from each other in terms of scale, jargon, and topics. The topic we’re dealing with is the causes and impact of the pandemic across the total environment. Our 15 authors include social scientists, life scientists, and philosophers of science, both within and beyond the KLI, so we’re talking about issues ranging from health systems, capitalism, to epistemology. As it turns out, complexity is super complex! Looking at all the issues across the total environment and the diversity of proposed cases, where do we even start when it’s all so complex?

Our task is to create a joint focus and vision by identifying key points. To streamline this process, we’ve divided the project into four different sections (Innovation Systems, Health Systems, Land Systems, Knowledge Systems) and scheduled meetings between the section heads (Marco Vianno Franco, Marco Treven and Orsolya Bajer-Molnár, Jacob Weger, Christian Dorninger, respectively). Yet very quickly, we realized that even this smaller group meeting had interdisciplinary challenges—each person took away something different from the meetings. There were more divergences than convergences. This was natural, as different people and disciplines related to different aspects.

Lynn: What did you do to address this challenge?

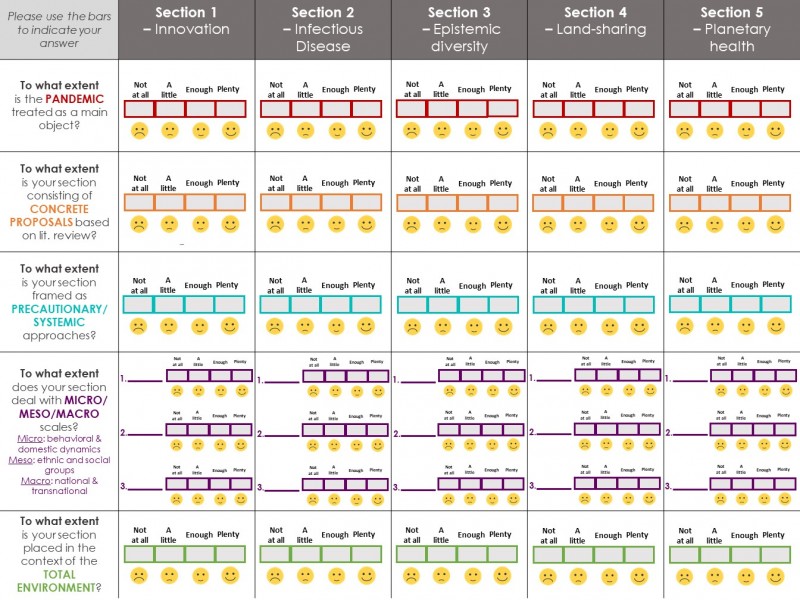

Orsolya: We decided to keep things grounded by creating a “thought anchor” that can maintain cohesion between the sections. The following chart helps each section keep track of the three main elements of the project, to ensure that we are explicitly dealing with issues where the pandemic is a cause, that the proposals we’re presenting are concrete (not “ifs,” not just an analysis, but actual outcomes with exemplary examples and cases), and that they are theoretical, precautionary (calling for preventive action before a crisis, instead of reactions), and systemic (not top-down from the Ivory Tower, but horizontally connected in dialogue with the multiple voices in society). We used emojis because they were naturally inviting. The chart was printed out as a physical poster and we stuck it on a big wall in the middle of the institute so that section heads could physically stand there and ponder through the questions.

Lynn: Looks like these rows helped the sections stay on track in terms of content. How did you create cohesion between the differences inherent in the various disciplines?

Orsolya: We added two more rows asking each section to consider the scale of their phenomena/solutions and to note down the keywords that connect them to the three different spheres (the biosphere, the geosphere, to anthroposphere) of the total environment. The former is to help the section leads oversee and understand the scale on which each section was operating on, whether it was more on a global, social or individual level. The three spheres remind us that each section should look for unanticipated consequences beyond their own realm, but at the end, we realized that everything links from and back to the anthroposphere.

Lynn: It seems to me that the “thought anchor” not only served a converging role to help each section work towards a common and cohesive goal, it also played a generative role to create new questions and connections. What were some of the new challenges that arose from this method, though, or challenges that were still difficult to resolve?

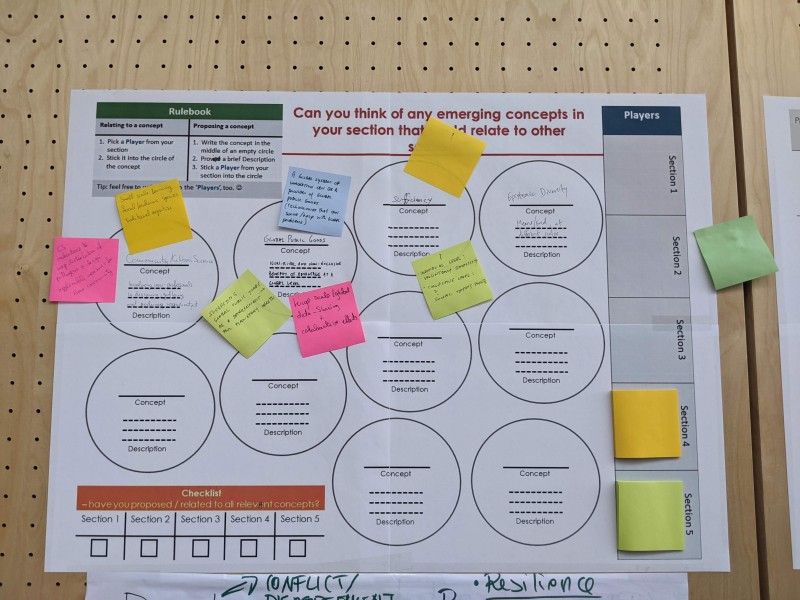

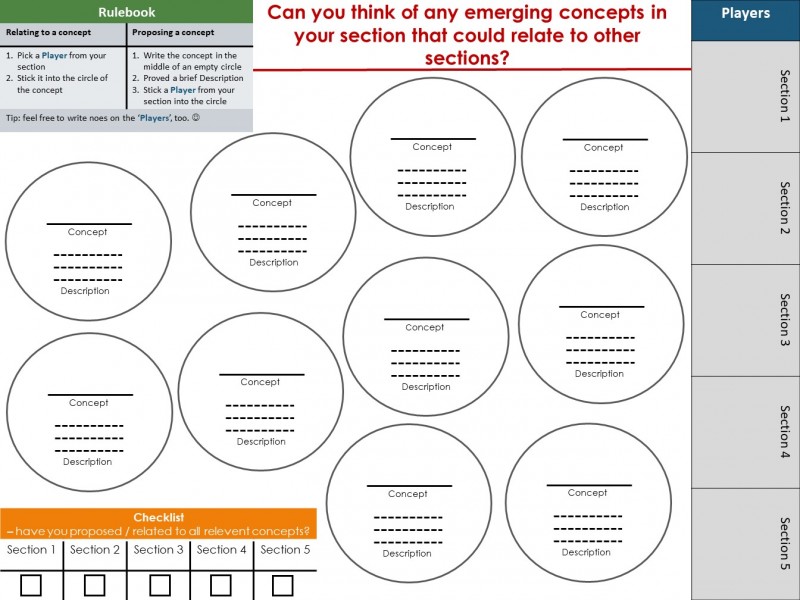

Orsolya: The thought anchor helped us find common concepts centered around the pandemic, offering proposals as solutions that take a systemic, precautionary stance. To acknowledge the concepts that had emerged in the process and further recognize aspects of cohesion between divergent fields, though, we needed to do more. Therefore, we developed a second activity, a concept relation “game” with a new chart and colored post-it notes. Each “player” (section members) is assigned a stack of post-it notes in their own color. Step 1 of the procedure is to answer, “Can you think of any emerging concepts in your section that could relate to other sections?” by writing a concept on the circles and posting their post-it notes next to it, signaling the section that suggested the concept first. Step 2 is to find a “concept circle” that had already been proposed and stick one of their post-its there as well, signaling connection and convergence. We gave the team members two weeks to work through this poster. Common concepts that emerged include “citizen science” or “bottom-up participation” and “global public goods” or “global health.”

Lynn: It almost looks like a boardgame! What were some of the advantages of this practice?

Orsolya: It was indeed inspired by table-top games. First, it was practical. It helped us anticipate possible reviewer comments about the tightness of the paper. Second, it was epistemically generative. It helped us discovery important connections across disciplines and created the structure for our final remarks.

Lynn: If another interdisciplinary team were to want to apply your two tools (the thought anchor chart and the concept connection game), what suggestions would you have for them? What are the limitations of your method?

Orsolya: Different issues require different approaches. It is one thing for a transdisciplinary team to gather evidence to support a theory. It is another thing to call attention to a method or approach (e.g., systemic, precautionary, proactive), which was the aim of our paper. We needed to figure out how we could simplify the complexity of our topic. The more connections and reflections we made about the total environment, the more difficult it is to not consider just… everything. When we do that, our bubble of concern becomes so big, it becomes smoke all around us!

Those seeking to replicate our process should note the contingency of our tools. First of all, these two tools arose from the process to resolve the immediate issues we had. They were concocted on the go, not created before the project. Secondly, what made them usable for us was the fact that it’s about the current pandemic, which is a central, all-encompassing, definite, and highly relatable problem with multiple subtopics. Taking these contingencies into account, my suggestion would be more general: (1) remain observant of emerging issues and challenges that come from your specific process and (2) develop flexible co-working methods that not just address these issues but are also more generative. This would be my main take-away.

Finally, we created a hierarchy (members, section leaders, project co-leads) to manage agreements and disagreements, but still, we probably hit the maximum amount of people to make this work.

Lynn: I find your response inspirational in two ways. First, I am impressed by the way you and your team developed the right kinds of tools for the project and I think that deserves to be shared. But secondly, I am also impressed by your honesty and humility. Indeed, it would be hubris to assume that one solution or tool can solve all trans-disciplinary problems. This is a fantastic take-home message, that one should cultivate the right kind of self-awareness and flexibility to know how when and where and how to develop epistemically generative tools. Thank you so much for sharing the back-story with us, Orsolya. It was incredible to witness this process and I hope that readers interested in engaging with interdisciplinary work will find some useful gems in this interview!

Publication